Age in the code – How algorithms turn life stages into data

Platforms no longer just record age. They model it. Behavior becomes probability.

Probability becomes decision. What role should age play in code going forward And who gets to define what counts as normal?

Age as an organizing principle of modern societies.

Discord has announced that it will no longer rely solely on self-reported information to determine users’ age, but will instead infer it from behavioral patterns. The system derives an age probability from usage data, interaction patterns, and technical parameters.

The stated goal is youth protection. The intention is legitimate. Digital spaces urgently need reliable safeguarding mechanisms.

At the same time, this decision signals a broader shift.

For a long time, age was treated as a constant. A date. A number. An administrative fact. You are born, you are counted, you are classified. School eligibility. Voting rights. Retirement. Life stages arranged in a clear sequence.

The year of birth structured biographies, institutions, and markets. It was imprecise, but stable. And that stability was never neutral. It determined who was granted responsibility early—and who was told to wait.

In digital systems, that stability is beginning to dissolve. Age moves from form fields into models. From self-declaration into statistical inference.

Digital systems transform age from a declaration into an attribution.

It’s not only Discord that analyzes interaction patterns, account histories, and technical parameters to infer users’ age and generate an age probability model.

OpenAI has also indicated that, in the context of ChatGPT, age may be inferred rather than simply declared.

And Spotify offered a softer version of the same logic at the turn of the year, translating listening habits into a personalized “musical age” — modeled through aesthetic preferences.

When age is calculated, the power to define it shifts.

Research makes clear that this development is not trivial. The risk that age stereotypes become embedded in training data and reinforced by models is well documented.

In AI ethics, this is increasingly discussed under the term “algorithmic ageism.”

Studies suggest that AI systems can reproduce age attributions even when age was never explicitly programmed. Bias emerges from the data environment and from model architecture.

Models learn from historical usage data, text corpora, interaction patterns, and platform logics. If certain age groups appear more frequently in connection with specific topics, styles, or roles, these patterns become statistically stable. The model learns correlations, not intentions. It detects repetition and amplifies it.

This shifts the focus. The key question is no longer only how a model was programmed, but what kind of reality it was trained on. Who is visible in the dataset? Who is missing? Which assumptions about age are already encoded implicitly?

Age models are built on assumptions about what is considered “typical.”

Which language patterns are treated as indicators of being underage?

Which interaction density is read as a sign of maturity?

Which topics are considered age-appropriate?

From such assumptions, training data is formed.

From training data, models are built.

From models, decisions are made.

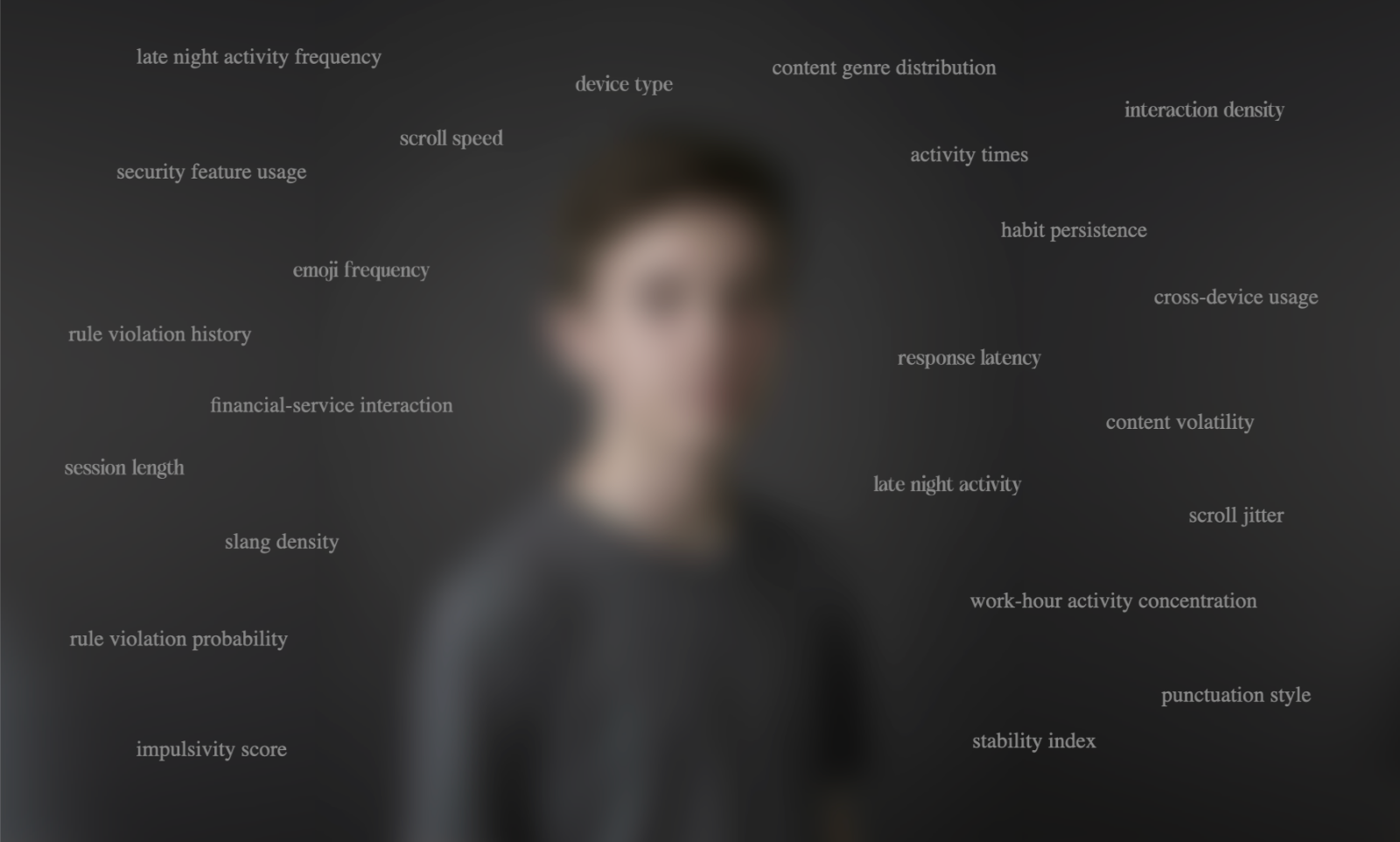

In this way, a particular image of age becomes embedded in technical infrastructure and reconstructed through proxy variables: writing style, emoji use, music references, interaction frequency, time of day, device choice.

These markers are culturally shaped. They reflect how certain groups communicate, which platforms they use, and which references they share.

When such patterns are treated as proof of age, a cultural style is reinterpreted as an individual attribute.

The idea of inferring age from behavior predates AI.

Age inference models may seem like a product of recent AI advances. In fact, the underlying logic goes back much further.

As early as 2006, computer scientist and machine learning researcher Jeffrey Schler, together with colleagues, examined whether age could be inferred from blog texts. The results revealed statistically significant patterns.

In 2013, computational social science researcher H. Andrew Schwartz analyzed millions of social media posts. Here too, the findings showed that age can be reconstructed probabilistically from linguistic patterns.

The roots lie in computational linguistics and quantitative behavioral analysis. AI does not invent this principle. It intensifies it. More data. More complex models. Greater computational power.

The underlying assumption remains the same: behavior produces patterns that can be statistically analyzed.

Between statistical observation and operational infrastructure, there is a rupture.

That age can be modeled is empirically supported. In research contexts, a model output remains a probability with a margin of error. Once it feeds into platform architectures, it becomes a basis for decision-making. Access or restriction. Visibility or invisibility. Approval or limitation.

This is where the cultural dimension begins.

Correlation is not identity.

Probability is not essence.

Statistics are not character.

When language patterns correlate with age groups, they do not define an individual. Models abstract. They aggregate. They simplify. And every simplification determines what is considered relevant. What began as statistical analysis in research becomes decision architecture in digital systems.

When age is operationalized, it becomes part of power architectures.

Studies on age estimation in AI systems show significant differences in error rates depending on the dataset and the group in question. When training data lacks diversity or age is inferred primarily through proxy features, systematic distortions emerge.

Invisible in the interface. Effective in the background.

If certain age groups are underrepresented in a dataset, the issue goes beyond higher error rates. A structural imbalance emerges. Models become more precise for dominant groups, while others remain statistically blurred.

That blur is invisible in the interface, yet operationally effective. It shapes access, visibility, and risk assessments.

Spotify represents the softer version. A playful mirror that reads curiosity as youth and nostalgia as older age.

Discord and ChatGPT represent the operational version. Here, the attribution shapes what you are allowed to do.

Protective mechanisms are necessary.

And platforms carry responsibility.

Age is a social category with a history. It structures power, access, and relevance. When it is translated into code, that process cannot remain opaque. Automated decisions must be transparent and contestable. Otherwise, infrastructure turns into a black box.

The crucial questions are straightforward.

How high is the error rate?

Who is systematically modeled with less precision?

How are edge cases handled?

And what is age ultimately used for — protection or sorting?

The shift from a birth date to a probability changes how we understand identity.

This is where the real shift occurs.

Age used to function as an administrative marker. A fixed value. Now it becomes a context-dependent category. No longer simply recorded, but modeled.

This opens up new degrees of flexibility. Life stages lose some of their rigid sequencing. Access can be shaped more by behavior than by the age entered in a form.

Classification does not disappear. It shifts.

Instead of clear age thresholds, statistical patterns take effect. Instead of fixed cutoffs, probabilities operate. New compartments emerge, less visible but still structuring.

This is not a radical break. It is a technological intensification of existing logics. Credit scoring and recommendation algorithms have long operated with implicit assumptions about life situations.

Age was never neutral. Now it is calculated systematically.

The question of age in code is ultimately a question about how we understand the human being.

What role should age play in digital infrastructures?

A threshold for access.

A protective mechanism.

Or an invisible logic of sorting.

What matters is not that such models exist. What matters is how they are embedded.

Age attributions must not become silent decision criteria whose underlying assumptions disappear into the system.

If age is calculated, it must be clear for what purpose, on the basis of which data, with which margins of error, and under which constraints. Once probability becomes infrastructure, the scope for action shifts.

Age in code shapes who are classified as mature, risky, or relevant. Whether age protects or filters is not decided in the interface, but in model architectures, training datasets, and product decisions. Modeling is selection. Selection is reduction. Reduction rests on data.

Whoever defines datasets and accepts certain correlations shapes the image of age within the system. Technical architecture is always a cultural statement.

The question is not whether age can be calculated.

The question is what that calculation comes to mean.

Where calculation begins, responsibility begins.

When age becomes a variable, technical precision is not enough.

What matters are the conditions under which that variable operates.

Transparency.

Which data underlies the model? Which assumptions shape it? Which margins of error are accepted? A calculated age must not be a black box.

Purpose limitation.

Does the attribution serve protection, or does it become a silent sorting criterion for visibility, prioritization, and risk assessment?

Contestability.

Can a probability be corrected, or does it solidify into identity?

If these conditions are missing, calculation quickly turns into selection. And that is where it is decided which form of “normality” we establish in digital systems.